Elizebeth Smith Friedman (spelled that way by her mother, who reportedly disliked the name ‘Eliza’) was born the youngest of 9 children in 1892. From a young age it was clear the girl was bright, displaying an impressive talent for languages. She wanted to go to college, so badly that she borrowed the money from her father at a 6% interest rate when he refused to pay for her schooling outright.

She finished school at Hillsdale College in Michigan, earning a degree in English Literature while also studying German, Greek, and Latin and discovering a love for Shakespeare that would last the rest of her life. It turned out that a career in education wasn’t for Elizebeth, who grew bored and quit her job as a principal before traveling to Chicago in 1916.

While there, she visited the Newberry Library, where Shakespeare’s First Folio was on display, and she ended up with a job at a nearby research facility, Riverbank. It was run by eccentric George Fabyan and already employed Shakespeare scholar Elizabeth Wells Gallup, who was working to prove that Sir Francis Bacon actually wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

Gallup was in need of a research assistant, and our Elizebeth was happy to take the job. She worked on a cipher that Gallup claimed was hidden in Shakespeare’s sonnets that proved they were written by Bacon, but perhaps more auspiciously, she met, fell in love with, and married geneticist William Friedman while there. A month later, the United States entered World War I.

Riverbank was one of the first institutes in the country to focus on codebreaking, or cryptology, and was essential in the early days of the war. It would transform both of the Friedman’s lives, with William becoming one of the biggest names in cryptanalysis (a word he coined himself) while his equally-as-talented wife was often deliberately kept from the spotlight.

“So little was known in this country of codes and ciphers when the United States entered World War I, that we ourselves had to be the learners, the workers, and the teachers all at the same time,” wrote Elizebeth in her memoir.

One of their more famous wartime accomplishments actually involved cracking a code for Scotland Yard – a trunk of mysterious, coded messages turned out to contain the secrets behind the Hindu-German Conspiracy, in which Hindu activists living in the United States were shipping weapons to India with German assistance.

The resulting trial was one of the largest in U.S. history (at the time) and ended sensationally as a gunman who believed one of the defendants had snitched opened fire in the courtroom.

After the war, the Friedmans moved to Washington D.C. and continued working for the military full-time. Elizebeth stayed home for a time to focus on raising the couple’s two children, but she returned to work for the Coast Guard in 1925 when they asked for help on Prohibition-related cases. There, she proved to be an invaluable asset, and was called to testify in a 1933 trial following the bust of a million-dollar rum running operation in the Gulf of Mexico and on the West coast.

During the trial, attorneys asked her to prove how a jumble of letters could possibly be determined to mean “anchored in harbor where and when are you sending fuel?” Elizebeth asked for a chalkboard and proceeded to give the court a lesson on simple cipher charts, mono-alphabetic ciphers, and polysyllabic ciphers, then reviewed how she had spent two years intercepting and deciphering the radio broadcasts of four illicit New Orleans distilleries.

Special Assistant to the Attorney General Colonel Amos W. Woodcock wrote that Elizebeth’s proficiency “made an unusual impression.”

A year later, Elizebeth used her skills to avert a court case between Canada and the United States when her codebreaking abilities proved that a “Canadian” ship sunk by the U.S. Coast Guard was actually a ship owned by an American bootlegger and simply flew the Canadian flag to avert suspicion. The Canadians were so impressed with her that they hired her to help catch a ring of Chinese opium smugglers, and her testimony in that case led to five convictions.

When WWII began, Elizebeth was recruited by the Coordinator of Information, an intelligence service that preceded both the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) and the CIA. While her husband, William, was lauded for leading the team that cracked Japan’s Purple Encryption Machine, Elizebeth’s accomplishments breaking German codes and working closely with British intelligence to disrupt Axis spy rings all across Europe. For years, researchers hit brick wall after brick wall trying to uncover her contributions, largely because J. Edgar Hoover wrote her out of history (or tried to) by classifying her files as top-secret and taking the credit for himself.

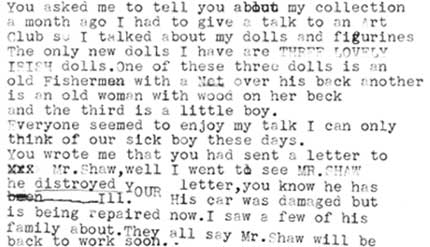

We do know, however, that she was instrumental in solving the “Doll Woman Case” in 1944, in which Velvalee Dickinson, a New York City antique doll dealer, was found guilty of spying on behalf of the Japanese government. Her work helped prove that the letters the woman had written about the condition of antique dolls were actually describing the positions of U.S. ships and other war-related matters. In the newspaper accounts of the day, however, Elizebeth’s name was never mentioned.

She retired in 1946, a year after the war ended, and her husband followed suit a decade later. Their relationship was uniquely bonded by their shared fascination for codes and codebreaking, which they brought into their person life as well – they used ciphers playing family games with their children and would even encode menus at dinner parties, encouraging their guests to solve them in order to earn the next course.

Together, they published The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined, a masterwork that won awards from several Shakespeare research facilities, and believed that they disproved the theory that Sir Francis Bacon was the real author of the plays.

William passed away in 1969 and Elizebeth spent her remaining years compiling and documenting her husband’s work in cryptology instead of going back over her own extraordinary achievements. Her writings are now part of the George C. Marshall Research Library.

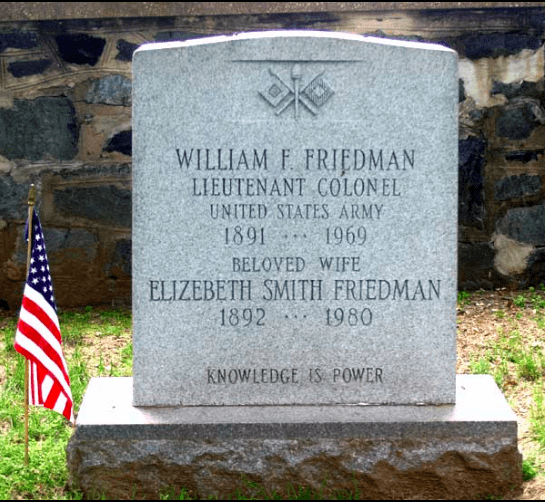

Elizebeth died in 1980 and is buried next to her husband. On their double gravestone is a quote commonly attributed to Sir Francis Bacon, “KNOWLEDGE IS POWER.”

The quote is, of course, a cipher that, when decrypted, reads “WFF,” William’s initials.

There’s no doubt that the field of codebreaking wouldn’t have come as far as fast as it did without William’s efforts, but Elizebeth’s deserve equal, if not more, credit.

The post The Incredible Story of Elizebeth Friedman, One of America’s Best Codebreakers appeared first on UberFacts.